Key Takeaways

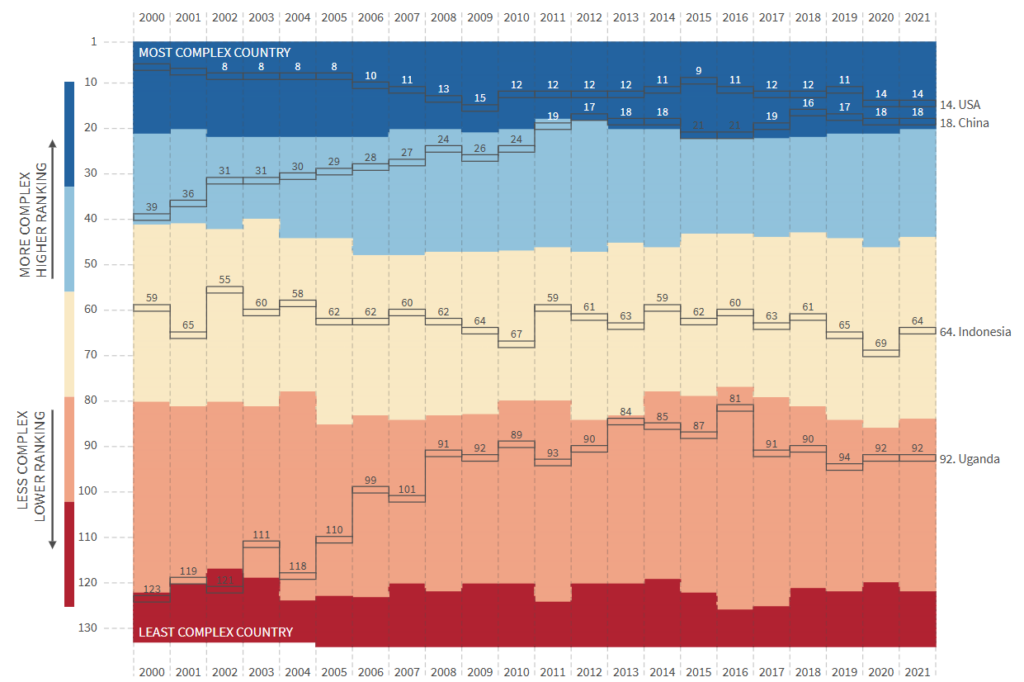

- Australia ranks 93rd on the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) (2021), lagging behind nations like Uganda, Guatemala, and Kenya. This ranking highlights a failure to diversify the economy.

- In the 2022–23 financial year, 66% of Australia’s export revenue came from mining, generating $455 billion—but the sector employs just 2% of the workforce.

- Australia’s economic dependence on China is a significant risk, with the nation purchasing more than a third of Australia’s exports.

- Emerging industries such as critical minerals (e.g., lithium, rare earth elements) offer potential but cannot fully offset declining demand for coal and gas.

- Tourism contributed $138.5 billion in visitor spending pre-pandemic, while international education was worth $41 billion annually—but both sectors remain fragile and highly dependent on international markets.

- Comparatively, countries like Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore have diversified their economies through innovation, technology, and strategic investment, providing blueprints for Australia’s future.

What Is Economic Diversity in Australia?

Economic diversity means having a wide range of industries contributing to the economy, not just relying on mining or raw materials. A diverse economy is more stable, better prepared for global challenges, and creates more jobs. But Australia has fallen short.

Australia is a long celebrated as the “lucky country,” that owes much of its prosperity to an abundance of natural resources. Its mining sector generates billions in export revenue, making the nation one of the wealthiest in the world. However, Australia’s economy is dangerously one-dimensional, leaving it exposed to global shocks and an uncertain future.

In 2021, Australia ranked 93rd on the Economic Complexity Index (ECI), lagging behind countries such as Guatemala and Kenya. This ranking measures a country’s ability to produce diverse and sophisticated goods—a marker of economic adaptability and resilience. Despite being the 13th largest economy globally by GDP, Australia’s ECI ranking paints a bleak picture of a nation overly reliant on raw material exports. For a country of its wealth, this is a glaring underachievement.

Australia’s lack of economic diversity is a ticking time bomb. Over 66% of its total export revenue in the 2022–23 financial year came from the mining sector, with coal and iron ore dominating the portfolio. This heavy dependence has made the nation acutely vulnerable to price volatility, global market shifts, and geopolitical tensions. The overreliance on China—purchasing more than a third of Australia’s exports—further intensifies these risks.

Should demand for fossil fuels decline or political relations sour, the economic consequences could be devastating.

Australia’s Economy Ranking

At first glance, Australia’s GDP ranking might seem impressive. But the reality is less rosy.

Mining has been the backbone of Australia’s economy, contributing a record-breaking $455 billion in export revenue in 2022–23, but its dominance is both a strength and a weakness. The sector employs just 2% of the national workforce, highlighting the uneven benefits it delivers. Mining booms enrich select regions while leaving others behind, creating economic disparity and instability.

Moreover, the environmental and geopolitical landscape is shifting rapidly. As countries transition toward renewable energy, global demand for coal and gas is expected to drop. While critical minerals like lithium and rare earth elements offer growth opportunities, they cannot fully replace the revenue generated by traditional mining exports. This looming transition underscores the urgent need for economic diversification.

What Type of Economy Is Australia?

Australia has a mixed economy, meaning it combines private businesses with government involvement. But this structure hasn’t helped it move beyond its reliance on raw material exports like coal, iron ore, and gas.

Fragile industries like tourism and international education have tried to balance mining, but they face big challenges. Tourism brought in $138.5 billion annually before the pandemic, and international education was worth $41 billion annually. Yet both industries rely heavily on international markets, making them unstable. Border closures during COVID-19 revealed how quickly these sectors can crumble.

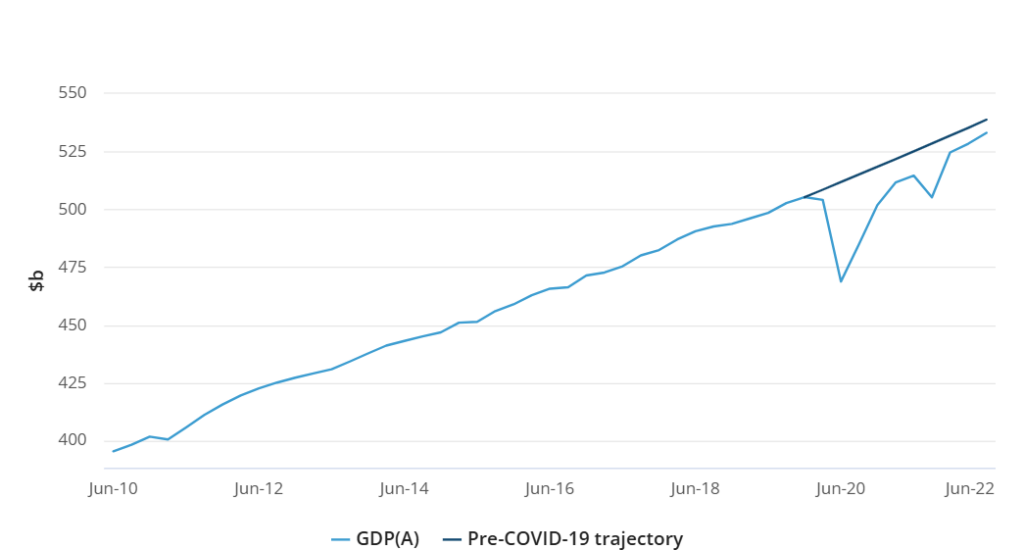

Australia’s GDP experienced a cumulative loss of $158 billion compared to its pre-pandemic trajectory, as reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This downturn was primarily driven by record declines in household consumption during nationwide lockdowns.

The broader economic picture also highlights Australia’s struggles. Katherine Keenan, Head of National Accounts at the ABS, stated:

“GDP growth was weak in March, with the economy experiencing its lowest through the year growth since December 2020.”

Furthermore, Westpac’s economics team noted that the annual pace of growth is “well below trend and the slowest outside of recessions and the major shocks of the pandemic and the GFC.” This represents the lowest GDP growth in over 30 years outside of the pandemic. They added:

“It is particularly weak given the current strong pace of population growth, running at 2.4 per cent per year. Australia has now recorded four consecutive quarters of declining per capita GDP.”

These figures emphasise the ongoing vulnerabilities in the Australian economy. While population growth accelerates, declining per capita GDP indicates that economic gains are not being shared equally or efficiently across the nation.

Economic Issues in Australia: Lessons from Global Leaders

Australia’s struggles with economic complexity stand in contrast to nations like Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. These countries have transformed their economies by investing in innovation and high-value industries:

- Switzerland ranks among the highest on the ECI, excelling in finance, pharmaceuticals, and precision manufacturing. Its balanced and innovative economy protects it from global shocks.

- Japan, despite lacking natural resources, thrives on advanced manufacturing and technology. By continuously evolving its industries—such as transitioning from consumer electronics to robotics and AI—Japan has remained globally competitive.

- South Korea has transitioned from an agricultural economy to a leader in technological innovation, dedicating over 5% of its GDP to research and development (R&D) in 2022. Companies like Samsung and LG showcase the success of sustained investment in cutting-edge technologies and long-term innovation.

- Singapore has built a thriving economy through strategic trade, finance, and logistics. Its world-class education system and business-friendly policies attract talent and investment from around the globe.

These examples highlight what Australia could achieve if it prioritised diversification and innovation over short-term resource dependence.

The Crossroads: Adapt or Stagnate

Australia is at a turning point. It can stick with its mining-driven economy, reaping short-term gains, or take bold steps to transform for the future. Staying reliant on raw material exports may seem easy now, but it leaves the country vulnerable in the long run.

The better choice is to invest in renewable energy, advanced manufacturing, and technology—industries that promise sustainable growth. With abundant natural resources and a strategic location near Asia, Australia has everything it needs to lead in these sectors. But without strong leadership and a clear plan, these opportunities could slip away.

A Call for Change

The cracks in Australia’s economy are widening. A reliance on mining has left the nation vulnerable to the dual threats of global market shifts and geopolitical tensions. Meanwhile, its economic complexity ranking—one of the lowest among developed nations—signals a lack of adaptability. Without significant diversification efforts, Australia risks falling further behind as the world moves toward renewable energy and advanced technologies.

The need for change is urgent. By learning from global leaders and leveraging its unique strengths, Australia can build a more balanced, resilient economy. This isn’t about abandoning mining—it’s about ensuring that the nation’s future isn’t tied solely to the fortunes of a single industry.

The “lucky country” has relied on luck for too long. Now, it must chart a new course—one driven by innovation, adaptability, and a commitment to securing its economic future.